A Quick Guide to Dialing in Espresso

Published:

Understanding the brewing process is the key to good coffee!

Introduction

If you are a coffee lover and you happen to make your own espresso at home, you must have read about the so-called gold standard of extracting about 1:2 yield ratio within 25 to 30 seconds. However, do you know which variables to tweak when your espresso does not look good or taste good? If you don’t, I believe you will after reading this blog.

Variables to Play with in the World of Espresso

In espresso making, there are many variables you get to play with, and each contributes to your final cup of coffee. Some basic ones include grind size, the amount of coffee you use, the type of coffee beans you use, water temperature and yield. To pull a decent espresso shot, you’ll need to tune these variables to ahieve the best flavor.

But before I get into each one of the variables, let’s first think about what’s really happening in the brewing process. If you use a semi-automatic espresso machine, the usual workflow would be

- grinding coffee beans

- puck prep and tamping

- locking in the portafilter and letting water through

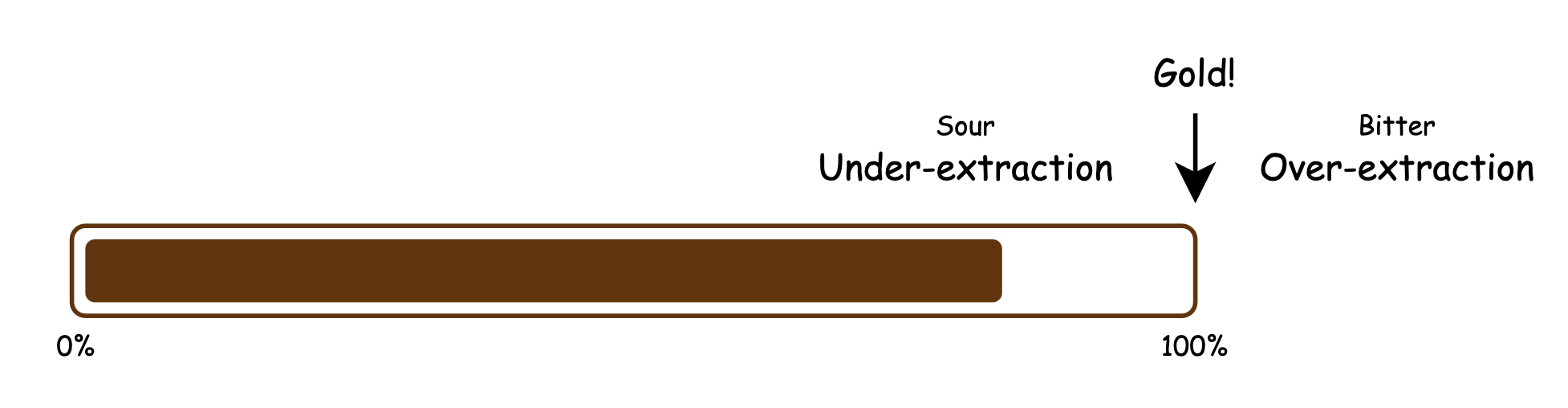

Essentially, the extraction process allows water, as a solvent, to resolve the chemicals within the coffee and bring them into the cup. The tricky part is to know the extent the coffee is extracted. Just like cooking a steak, you have to know when to stop the heat to prevent either undercooking or overcooking. There are exact matching terms in espresso, that are under-extraction and over-extraction (See the illustration below).

Then the question becomes: how is extraction impacted by various variables? Here I present each variable in the table below so you get a sense of how each one of them contribute to the extraction before I go through them one by one.

| Variable | Easier to extract / More extraction | Harder to extract / Less extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Roast level | Darker | Lighter |

| Amount of coffee | Less | More |

| Grind size | Finer | Coarser |

| Water temperature | Higher | Lower |

| Pressure | Higher | Lower |

| Extraction time (also yield) | Longer | Shorter |

Roast level

The conclusion is that darker roasted coffee are generally easier to extract than lighter roasts. This is because as the roasting process continues, the structural integriry of coffee beans degrades and they become more porous, which means the contact surface with water during extraction increases and soluables are easier to be brought out by water. As a side note, dark roasts usually exhibit flavors such as caremel, nuts, and chocolates, and the espresso they yield often looks creamy and syrupy.

With that in mind, it is intuitive to know that dark roasts often require a coarser grind size than light roasts because once ground too fine, bitterness would take over (over-extracted). What’s also a common practice is that people usually use hotter water for light roasts because soluables are usually easier to dissolve when the temperature is higher (basic chemistry).

Amount of coffee

This attribute refers to the dose of coffee beans you use for your shot of espresso, which is usually 18 grams. However, we can sometimes tweak the dose by 0.x grams to achieve certain effects. The dose of coffee can be seen as the total amount of work to do. Intuitively, with more coffee grounds in the basket, there’s more work to do for extraction, and vice versa.

Generally, I would recommend you to use the dose that is labeled on your basket. However, if there’s no dose specified on it, I suggest you do the following.

- Fill your basket with coffee beans as much as you can.

- Weigh the beans inside the basket and that’s about the dose you should use.

Grind size

Grind size is probably the variable that has the most impact on espresso as it’s essential to whether or not your coffee puck can take on enough pressure from the water. If ground too coarsely, the coffee puck won’t be able to form valid resistance against the water that pushes down and thus you are likely to get a fast, low-pressure (under 9 bar), under-extracted, sour cup. On the contrary, if ground too finely, the coffee puck will become too solid for the water to penetrate, and you will get a long, high-pressure (over 9 bar), over-extracted, bitter cup.

Water temperature

Another variable that is not so commonly considered by beginners is water temperature, as most home espresso machines does not support adjustments of it. Still, I’ll list it here and discuss it. In chemistry, we know that the solubility of most substances increases when temperature gets higher. The same applies in espresso making. With hotter water, it is easier to dissolve substances from coffee grounds. As a result, the common recipe is to use hotter water for “harder-to-extract” coffee (e.g., light roasts) and to lower the water temperature for “easier-to-extract” coffee (e.g., dark roasts).

Pressure (Note: What’s being discussed here is the pressure within the group head, instead of the pump pressure.)

Pressure is actually an induced variable, which is only dictated by how much resistance the coffee puck can generate against the water. To be more specific, it depends on grind size and flow rate. When you grind the beans finely, the coffee puck becomes dense and is hard for water to go through. However, the water comes out from the group head at a fixed flow rate. Now what happens when there’s constant water coming in and not that much water coming out? Pressure builds up. As the water starts wetting the puck and espresso starts dropping, the puck starts to lose its structural integrity due to the water flow. That’s why you see only drops of espresso coming out at the beginning of an extraction but a fast-running stream at the end.

Some machines, such as the Lelit Bianca and the La Marzzoco GS3, support flow control. That means you can adjust water flow rate dynamically throughout the extraction. Different levels of flow rate then result in (what is appears to be) different pressures. Other high-end machines such as the Rocket R9 One and the La Marzzoco Strada, support pressure profiling, which varies the pump pressure, i.e., the pressure that water is pumped to the group head.

General Principles for Dialing in Espresso

Enough for theories. Now how do we make a good espresso? Having a brand new coffee at hand, the first goal I suggest you set is the gold standard of extracting about 1:2 yield ratio within 25 to 30 seconds. Once you’ve done that, you can then make adjustments based on the taste. Here’s some advice.

Tune one parameter at a time

In scientific research, we hear about control variables all the time. The same thing applies here. Whenever you make adjustments, do remember to keep all other ones fixed. For example, if you choose to grind finer in the next shot, please keep dose (e.g., 18 grams) and yield (e.g., 36 grams) the same.

Prioritize taste over look

Another advice is something I’ve learned through my experience. I know that espresso making for some people (including me) is an aesthetic process where you get to watch beautiful syrupy espresso coming out slowly. However, good-looking espresso does not always taste good. Thus, do not judge your espresso primarily based on its look, but on its taste instead.